Humayun’s Tomb is the first of the grand dynastic mausoleums that became synonymous with Mughal architecture. Located in Delhi, it was at Humayun’s Tomb, where some of the prominent features of Mughal architectural style were established which reached its zenith 80 years later with the Taj Mahal. Over the years, Humayun’s tomb also came to be the resting place of more than 150 Mughal family members. A fine example of Persian architecture, which created a template for Mughal architecture, this beautiful mausoleum is also the resting place of Emperor Shah Jahan’s son Dara Shikoh, Humayun’s two wives and later Mughal emperors.

The Turco-Mongol prince Babur invaded India and defeated Ibrahim Lodi, the last Lodi Sultan and son of Sikander Lodi, in the First Battle of Panipat in 1526. This was the beginning of Mughal rule in India under Babur. Four years after he established his supremacy in North India, Babur died of a fever in 1530 in Agra. Babur’s son Humayun ascended the throne in 1530 at the age of 22. Humayun had a challenging time heading the newly-established Mughal territory. Humayun died in 1556 AD after a fall from stairs in his library.

Interestingly, Humayun’s tomb wasn’t the first resting place of the emperor. At first, Humayun was buried at his palace at Purana Qila in Delhi. Following his death, Delhi was attacked by Hemu, Chief Minister of Adil Shah Suri of the Suri Dynasty. To preserve the sanctity of their Emperor’s remains, the retreating Mughal army exhumed Humayun’s remains and took them to be reburied at Kalanaur in Punjab.

Image Credits: Wiki Commons

Humayun’s Tomb was built in the 1560s with the patronage of Humayun’s son, Emperor Akbar. However, according to some sources it was Humayun’s wife, either Bega Begum or Haji Begum, who commissioned the construction of the mausoleum. Persian and Indian craftsmen worked together to build the garden-tomb, far grander than any tomb built before in the Islamic world.

The 10-hectare (25-acre) plot on which the building stands was one of the first to have been laid out in a manner of Char Bagh (“paradise garden”). The garden is divided into four large squares by means of causeways and water channels. Each of the four squares is further subdivided in a manner so that the whole is subdivided into 36 smaller squares. The tomb occupies the four central squares. Inspired by the design, the English architect Edwin Lutyens recreated a similar design around the Rashtrapati Bhawan.

Image Credits: Wiki Commons

The tomb itself stands on a raised plinth, which has as many as 56 cells or small chambers on all four sides. Another striking feature of the tomb is the marble dome. The dome is probably one of the first double domes in the Indian sub-continent. A double dome consists of two layers, with a gap between them. The dome is flanked by chhatris or domed pavilions, and the domes of the central chhatris are adorned with glazed ceramic tiles. The main chamber under the dome houses Humayun’s cenotaph. The main chamber also carries the symbolic element, a mihrab design over the central marble lattice or jaali, facing Mecca to the West.

Image Credits: Wiki Commons

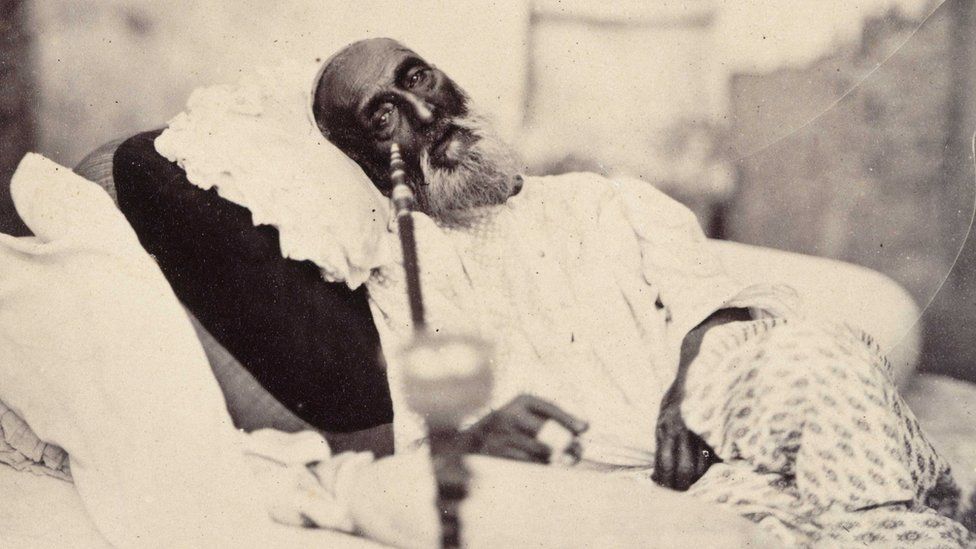

When the British captured Delhi during the revolt of 1857 and attacked the city of Shahjahanabad, the Mughal family had to leave the royal palace in the Red Fort. The royal family with Bahadur Shah Zafar, his wives and three princes took refuge at Humayun’s Tomb. A British military officer, Captain William Hodson, is said to have taken Bahadur Shah Zafar prisoner in September 1857 from Humayun’s Tomb. After that, he was taken to the Red Fort and exiled to Rangoon in 1858.

The mausoleum also witnessed the troubled times of the Partition of India in 1947. The tomb and its garden hosted refugee camps and provided shelter to families who immigrated to India from the newly partitioned Pakistan. The occupation by teeming refugees for about five years damaged the gardens and even the principal structures in the tomb complex. Humayun’s tomb was also granted the status of UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1993. The restoration of the mausoleum began after 1999 with a joint effort of the Archaeological Survey of India and Aga Khan Trust for Culture. Today, the mausoleum stands proudly amidst a serene garden of 12 hectares, echoing multiple voices from the past.