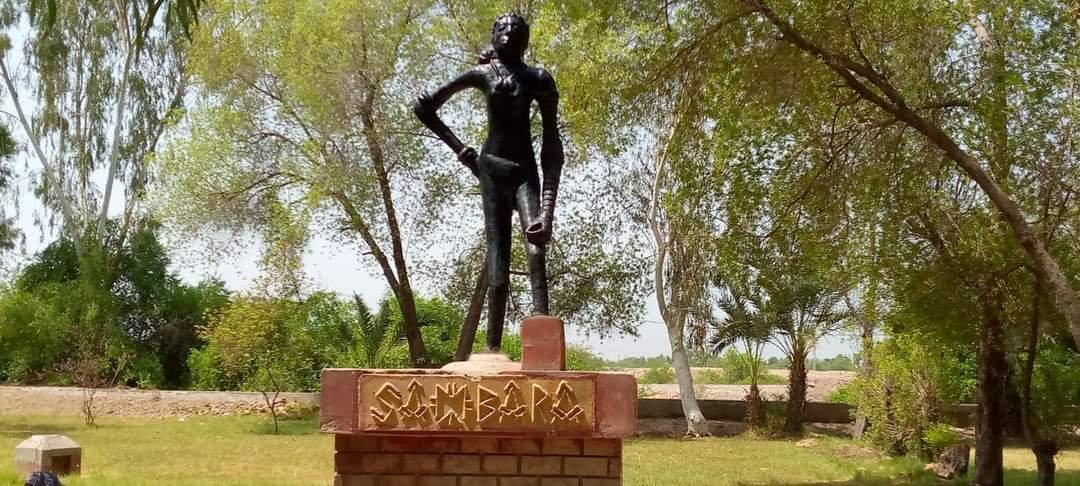

The sculpture of the “Dancing Girl” is perhaps one of the celebrated pieces of art in India. Shrouded in the mist of time, this Indus Valley sculpture has incited awe, controversy and global appreciation. One of the biggest achievements of the artists at Mohenjodaro, the bronze sculpture dates back to 2500 BCE. The sculpture was found by the famous Indian archaeologist Dayaram Sahni during his 1926-1927 field season at Mohenjodaro.

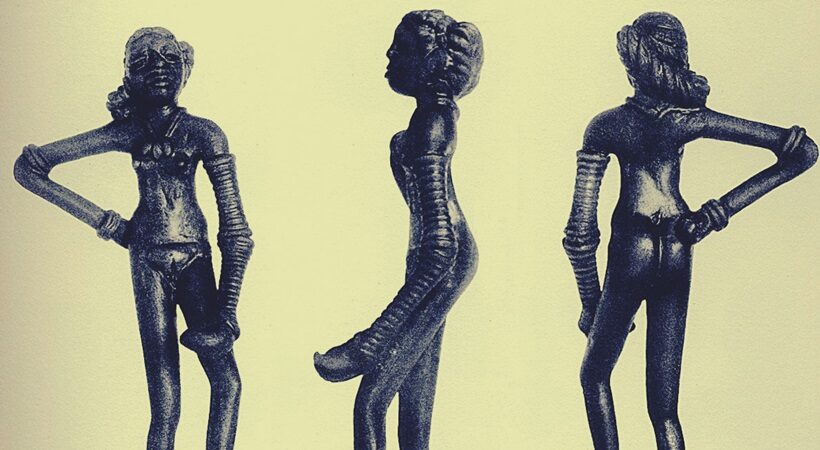

The Dancing Girl figurine was sculpted using the lost-wax process, which involves making a mold and pouring molten metal into it. The figurine is a naturalistic free-standing sculpture of a nude woman, with small breasts, narrow hips, long legs and arms and a short torso. She wears a stack of 24 bangles on her left arm. She has long legs and arms compared to her torso; her head is tilted slightly backward and her left leg is bent at the knee. On her right arm are four bangles, two at the wrist, two above the elbow; that arm is bent at the elbow, with her hand on her hip. She wears a necklace with three large pendants, and her hair is in a loose bun, twisted in a spiral fashion and pinned in place at the back of her head.

Due to the fragmentary and limited understanding of the Indus Valley Civilization, it is difficult to predict who and what this sculpture refers to. However, it is interesting to note the various interpretations of the sculpture, as in some cases the interpretations talk more about the politics and time-bound context of the scholars. The sculpture was originally catalogued as of a dancing girl, owing to its sinuous form and seemingly contrapposto stance signifying movement.

However, some critics consider this as an imposition of modern gender roles on 4500-year-old sculpture, as many unidentified sculptures are generally catalogued as “mother/fertility goddesses” or performers/attendants, where the socio-cultural structure could be more complex. Possibly, the sculpture might be depicting a working woman as the subject has switched all her bangles to one hand, perhaps allowing greater physical movement.

Other scholars like ECL During Casper have claimed that the physiological features of the sculpture suggest an African subject. There is recent evidence emerging of the ancient ties of the port of Chanhu-Dara with Africa, including one burial of an African woman and the founding of pearl millet at the site, which was domesticated 5000 years ago in Africa. The sculpture has also become a source for Hindutva politicking with a retired professor Thakur Prasad Verma from BHU publishing in an ICHR journal linking the sculpture with the figure of Parvati.

The sweeping claim mostly rests upon the assumption that the famous Seal 420 of “a horned figure in a seated posture and surrounded by animals” is a depiction of Shiva. However, the claim has been rejected by the scholarly community due to a lack of evidence.

Moreover, the sculpture has also been used to incite nationalist fervour in India and Pakistan. As the artifacts from then unified India were equally divided between India and Pakistan, the famous sculpture of “Priest-King” was sent to Pakistan and the Dancing girl was kept at the National Museum in Delhi. From time to time, politicians have claimed the sculpture as a part of their (Pak) national heritage inciting controversy.